Father’s day, June 19th, 2016, looming. Though it’s only a week away, it’s reared its head since January 20th, when my father died. Every year we met in Chehalis, halfway between Portland and Seattle. There was a Father’s Day years ago that for logistical reasons, neither of us could spend the whole weekend together – that is, me going to Portland, so we decided to meet and spend the day together at the Old Highway’s roadhouse inn, Mary McCrank’s. My father had discovered Mary’s in the war, travelling from his camp in Seattle to Portland when granted leave, on the only available road, Highway 99. Mary ran the kitchen in her old house and dished out the pan-fried chicken, a favorite dish of my dad’s, in the living and dining rooms. A measure of a good cook for my dad was one who (in that era, a woman) could crisp up perfect pan-fried chicken. We pursued pan-fried chicken at Nendel’s (Beaverton), The Gable (Corvallis), Rose’s and The Homestead (Seattle), West Linn Inn, Tad’s. But I’ve eaten the most pan-fried chicken at Mary McCrank’s, every Father’s Day for nineteen years.

Right on the old highway in south Chehalis, Mary’s house was set on a plush plot of grass with a small creek, a tiny bridge, benches, and oaks. Families took photographs in this setting after meals. Inside, the décor was “1940s frilly grandma” – lace tablecloths, antique knickknacks in every niche, colonial-scene wallpaper faded above pine wainscoting, the brick fireplace mantle lined with china cups and saucers. There was a bathtub in the women’s restroom, because yes, it really was her house.

The first two years we went, my father and mother were still married, and my roommate from college tagged along because her father had passed away. My mother would have something besides chicken, in her independent way, jealous of a cult food my dad and I both loved. The meal service was old-style – relish tray, homemade rolls and chutney, a salad or soup with the meal, also dessert included. We all asked for the creamed carrots, with their cloying sauce that leaked into the chicken, to be held. My dad always ordered a chocolate sundae, though it was not on the menu.

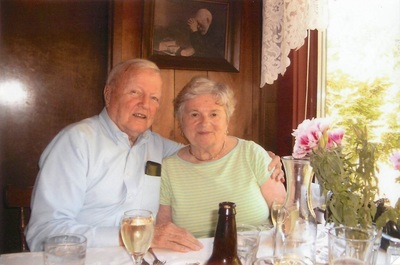

The crowd was dour small-town and every year we were the loudest table in the place, laughing at stories and my dad opening his presents. Always some old couples, where obviously the wife was taking the husband out for dinner, their grown children not around, to at least acknowledge his fatherhood. They ate in silence and the man often looked like coveralls were more his type of outfit. Families took the round tables, small children dressed for church and restless.

To extend the day after dinner, we took over a section of the backyard and set up a card table I brought. This was not the nice side part of the yard. This was a rotation of staff on breaks coming out to smoke, vent hoods snaking from the low, shingled backside of the house. Four folding chairs and a deck of cards. A cooler of beer and water for an hour or two of bridge, though we were mostly too full to imbibe. After the divorce, it was just Cathey, my dad, and me, and we played three-handed. Then my dad remarried and we initiated Mary Ellen into the scene. One year her son came up from California for the outing, so with five of us, we switched to dominoes. It was raining that year, and we sat under the potato-chip fiberglass patio cover with the inside diners looking on.

In 2010, we pulled up in the front (we never were more than ten minutes out of sync meeting) to find a huge expansion halfway done on the back and side of the house. That year it also rained, and the new owner let us to play cards within the fiberboard skeleton of the future.

The result of the construction was a large back room with plastic-wood floors that resembled the dining hall of a retirement home. Gone was the character and scale of the old Mary McCrank’s and whether you love lace or not, you still wanted that feeling. Lucky for us, the original front room was still in place with all the bric-a-brac, and we were always seated there. With the addition, they’d installed a bar and cocktails. Gin was often in short supply however, and it seemed to astonish the staff that all four of us might order martinis at once. While we were pleased to be in the original living room, we wondered about the business decision to expand a restaurant located in a tiny town on a forgotten highway. Three years later it was gone, the owners escaping to Utah after a suspicious fire.

Research had to be undertaken to save our Father’s Day, and I discovered a wonderful restaurant called Macinaw’s, in historic downtown Chehalis. Chef Laurel was not open on Sundays but agreed to. No fried chicken, but plenty of other good food in a town where choices are few. For the next three years our celebration was saved.

If Mary McCrank’s was still going, Cathey and I would meet again this year. We would drink beer and reminisce, eat chicken and ask for the carrots to be held. But Mary and her dreams are no longer. My father is gone. The day looms. I hope the dread will turn out to be nothing, because I’ve overthought the occasion. Not like my birthday when, waiting in line for coffee, I was completely caught off guard by the realization my father wouldn’t be calling me. Maybe Sunday I’ll fry a chicken, crispy on the outside, moist inside, see if I can measure up to those nineteen Sundays.

Right on the old highway in south Chehalis, Mary’s house was set on a plush plot of grass with a small creek, a tiny bridge, benches, and oaks. Families took photographs in this setting after meals. Inside, the décor was “1940s frilly grandma” – lace tablecloths, antique knickknacks in every niche, colonial-scene wallpaper faded above pine wainscoting, the brick fireplace mantle lined with china cups and saucers. There was a bathtub in the women’s restroom, because yes, it really was her house.

The first two years we went, my father and mother were still married, and my roommate from college tagged along because her father had passed away. My mother would have something besides chicken, in her independent way, jealous of a cult food my dad and I both loved. The meal service was old-style – relish tray, homemade rolls and chutney, a salad or soup with the meal, also dessert included. We all asked for the creamed carrots, with their cloying sauce that leaked into the chicken, to be held. My dad always ordered a chocolate sundae, though it was not on the menu.

The crowd was dour small-town and every year we were the loudest table in the place, laughing at stories and my dad opening his presents. Always some old couples, where obviously the wife was taking the husband out for dinner, their grown children not around, to at least acknowledge his fatherhood. They ate in silence and the man often looked like coveralls were more his type of outfit. Families took the round tables, small children dressed for church and restless.

To extend the day after dinner, we took over a section of the backyard and set up a card table I brought. This was not the nice side part of the yard. This was a rotation of staff on breaks coming out to smoke, vent hoods snaking from the low, shingled backside of the house. Four folding chairs and a deck of cards. A cooler of beer and water for an hour or two of bridge, though we were mostly too full to imbibe. After the divorce, it was just Cathey, my dad, and me, and we played three-handed. Then my dad remarried and we initiated Mary Ellen into the scene. One year her son came up from California for the outing, so with five of us, we switched to dominoes. It was raining that year, and we sat under the potato-chip fiberglass patio cover with the inside diners looking on.

In 2010, we pulled up in the front (we never were more than ten minutes out of sync meeting) to find a huge expansion halfway done on the back and side of the house. That year it also rained, and the new owner let us to play cards within the fiberboard skeleton of the future.

The result of the construction was a large back room with plastic-wood floors that resembled the dining hall of a retirement home. Gone was the character and scale of the old Mary McCrank’s and whether you love lace or not, you still wanted that feeling. Lucky for us, the original front room was still in place with all the bric-a-brac, and we were always seated there. With the addition, they’d installed a bar and cocktails. Gin was often in short supply however, and it seemed to astonish the staff that all four of us might order martinis at once. While we were pleased to be in the original living room, we wondered about the business decision to expand a restaurant located in a tiny town on a forgotten highway. Three years later it was gone, the owners escaping to Utah after a suspicious fire.

Research had to be undertaken to save our Father’s Day, and I discovered a wonderful restaurant called Macinaw’s, in historic downtown Chehalis. Chef Laurel was not open on Sundays but agreed to. No fried chicken, but plenty of other good food in a town where choices are few. For the next three years our celebration was saved.

If Mary McCrank’s was still going, Cathey and I would meet again this year. We would drink beer and reminisce, eat chicken and ask for the carrots to be held. But Mary and her dreams are no longer. My father is gone. The day looms. I hope the dread will turn out to be nothing, because I’ve overthought the occasion. Not like my birthday when, waiting in line for coffee, I was completely caught off guard by the realization my father wouldn’t be calling me. Maybe Sunday I’ll fry a chicken, crispy on the outside, moist inside, see if I can measure up to those nineteen Sundays.